Tackling erosion through tree roots and community

By Marisa Roefs, Stewardship Project Lead, Maitland Conservation

This year – like the spring before – I kneel in the mud, spade in hand. From my planting bag, I pull a White Oak seedling and immediately notice its already long, rigid taproot.

Before lowering it to the hole, I know I will have to dig deeper.

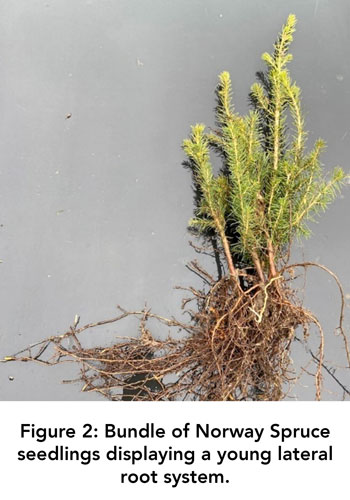

As I push the shovel further into the ground, I recall how simple it was to plant the Norway Spruce just eight feet away. With only two, quick slits in the ground, its short, flimsy roots had fit into place with ease.

Root Patterns

At just under two years old, both seedlings display something that will shape their growth and relationship with the soil for the rest of their lives: their root system – or root personality.

Anchors

Anchors

The White Oak has what we refer to as a taproot system: one dominant, deep-growing root, with smaller tendrils extending around it.

As the root grows further, the tree will rely on this sturdy anchor to hold it up during windstorms and to access water deep in the ground during seasons with little rain.

Thankfully, these anchors can hold more than just the tree. They can also act as pillars for large blocks of soil. In the right location and at the right density, taproot trees can stop these blocks of soil from moving and shifting.

Wide Networks

Wide Networks

The Norway Spruce, on the other hand, displays a lateral system: a shallow, branching array of roots that stretch away from the tree-trunk.

These trees attempt to hold themselves up with a wide, stabilizing base, rather than a deep one. Although the roots may grow deeper if needed, the shallowness can stop the tree from drowning during wet seasons.

These function as surface erosion control systems. The branching roots encourage soil particles to bind near the surface and protect them from the forces of wind and water.

The Hybrid

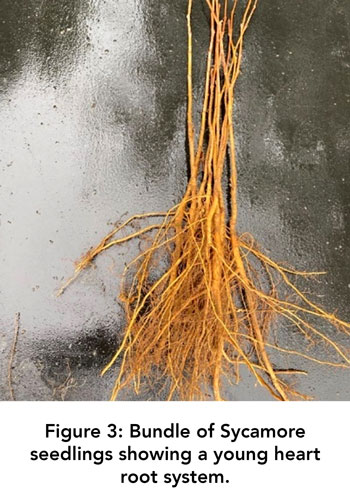

Not yet mentioned, or seen, is a third type of rooting system: a heart system. This pattern features a series of root like both taproots and lateral roots. The mixture of features comes with the functions of both explained above.

Not yet mentioned, or seen, is a third type of rooting system: a heart system. This pattern features a series of root like both taproots and lateral roots. The mixture of features comes with the functions of both explained above.

A Sycamore tree is a good example of a species with a heart root system.

Roots and Communities

Each root pattern aids the tree and soil in a unique way. But when the root systems begin to coexist, forming a diverse, interconnected network, is when things get interesting.

Trees of the same species may meet and join together; others will weave around their neighbour into complex matrices. Some will stay close to the surface, while others will reach depths their counterparts cannot. This tangle of roots becomes an underground community that holds the landscape together from below.

The root network is not so different from the community that holds together each planting season. Each tree is planted by the work of many hands:

- Seed collectors

- Nursery coordinators and staff

- Truck drivers

- Land managers including farmers, town residents, cottagers, and rural residents

- Engaged community groups and volunteers

- Tree planting professionals

- … and all the administrative bodies that provide funding through federal, provincial, municipal, and private means to make each project happen.

This network of dedicated people resulted in more than 15,000 trees planted in the Maitland Valley watershed this spring, with similar programs running along the Lake Huron shoreline in each watershed.

The goal is that these trees will root deep and withstand pressures long enough to form communities underground that hold our soil on the land and keep it from reaching the lake.

Interested in getting involved in tree planting?

Reach out to your local conservation authority or tree planting professionals in your area to find out more.